Venice had not yet become part of the Kingdom of Italy when Simeone Codognato opened his first workshop in 1866.

At just twenty-two, Simeone began his career as an antiquarian, specializing in the trade of old master paintings and decorative art objects. His clientele consisted largely of Grand Tour travelers—cultured aristocrats and intellectuals who visited Italy seeking beauty, history, and refinement. For them, Simeone curated pieces that captured the spirit of Venice: romantic, mysterious, and steeped in centuries of cultural heritage.

He chose a strategic location for his boutique, just steps from Saint Mark’s Square, the beating heart of the city. Though he began in the world of fine art, he soon extended his passion into the realm of jewelry, developing a distinctive decorative language that reflected the city’s timeless character. His pieces combined influences from Gothic, Byzantine, and Renaissance traditions—an eclectic fusion that foreshadowed the house’s signature style: expressive, symbolic, and uniquely Venetian.

As the annexation marked a new era of artistic and cultural vitality for Venice, Simeone’s workshop flourished. By the late nineteenth century, Venice was again a beacon of European creativity, celebrated by the launch of the Venice Biennale in 1895.

Attilio was deeply influenced by the era’s fascination with archaeology and antiquity. The great Etruscan excavations, along with the work of visionary goldsmiths such as Castellani in Rome and Giuliano in Naples, inspired him to explore a new creative path. He embraced the aesthetics of Italian Archaeological Revival Jewelry, fusing ancient techniques with a contemporary sense of drama.

In 1897, Simeone’s son Attilio Codognato inherited the business and, under his direction, the Codognato name shifted decisively toward high jewelry with a strong artistic identity.

Attilio was deeply influenced by the era’s fascination with archaeology and antiquity. The great Etruscan excavations, along with the work of visionary goldsmiths such as Castellani in Rome and Giuliano in Naples, inspired him to explore a new creative path. He embraced the aesthetics of Italian Archaeological Revival Jewelry, fusing ancient techniques with a contemporary sense of drama.

In 1906, Attilio introduced the now iconic skull-shaped jewels, known as Vanitas. These pieces were no mere ornament but a philosophical statement—memento mori that alluded to the impermanence of life and the enduring power of beauty. Crafted from precious materials such as coral, rock crystal, and gold, they embodied both refinement and provocation.

By 1910, Attilio’s talent earned him the title of First Goldsmith of Saint Mark’s Basilica—an honor that confirmed his place among Italy’s most respected artisans. His creations—serpent bracelets, moretto brooches, skull rings, and antique cameos—were hand-forged in the workshop using techniques inherited from Byzantium, Rome, and the Italian Renaissance. Each piece was a miniature narrative, saturated with symbolism and history.

As the twentieth century dawned, Venice’s reputation as a refuge for the culturally attuned only intensified.

The city became a sanctuary for a new wave of intellectuals, aristocrats, and artists who viewed it not just as a destination, but as a state of mind—somewhere between dream and decay. Figures such as Henry James, John Singer Sargent, and, later, Thomas Mann, found in its crumbling beauty a metaphor for the vanishing world of European grandeur. With the advent of luxury train travel, especially the Simplon Orient Express, Venice was no longer a remote marvel but a stop on the sophisticated traveler’s itinerary.

The Lido, once a quiet sandbar, was reborn as an exclusive seaside resort, its Art Nouveau hotels catering to the elite. Here, the season ran from May to September, and days were spent between shaded avenues, private beach clubs, and soirées at the Kurcasino. The city and the Lido together attracted a cross-section of Europe’s cultural elite: exiled Russian nobles, British socialites, German aesthetes, and American literati. They came for the light, the history, the atmosphere—but also to see and be seen.

For these discerning travelers, Codognato’s jewels, steeped in historical symbolism and charged with philosophical gravitas, were more than adornments—they were emblems of identity. In a place where beauty was always shadowed by impermanence, Codognato offered talismans that captured the city’s dual soul: dazzling and dark, opulent and ephemeral.

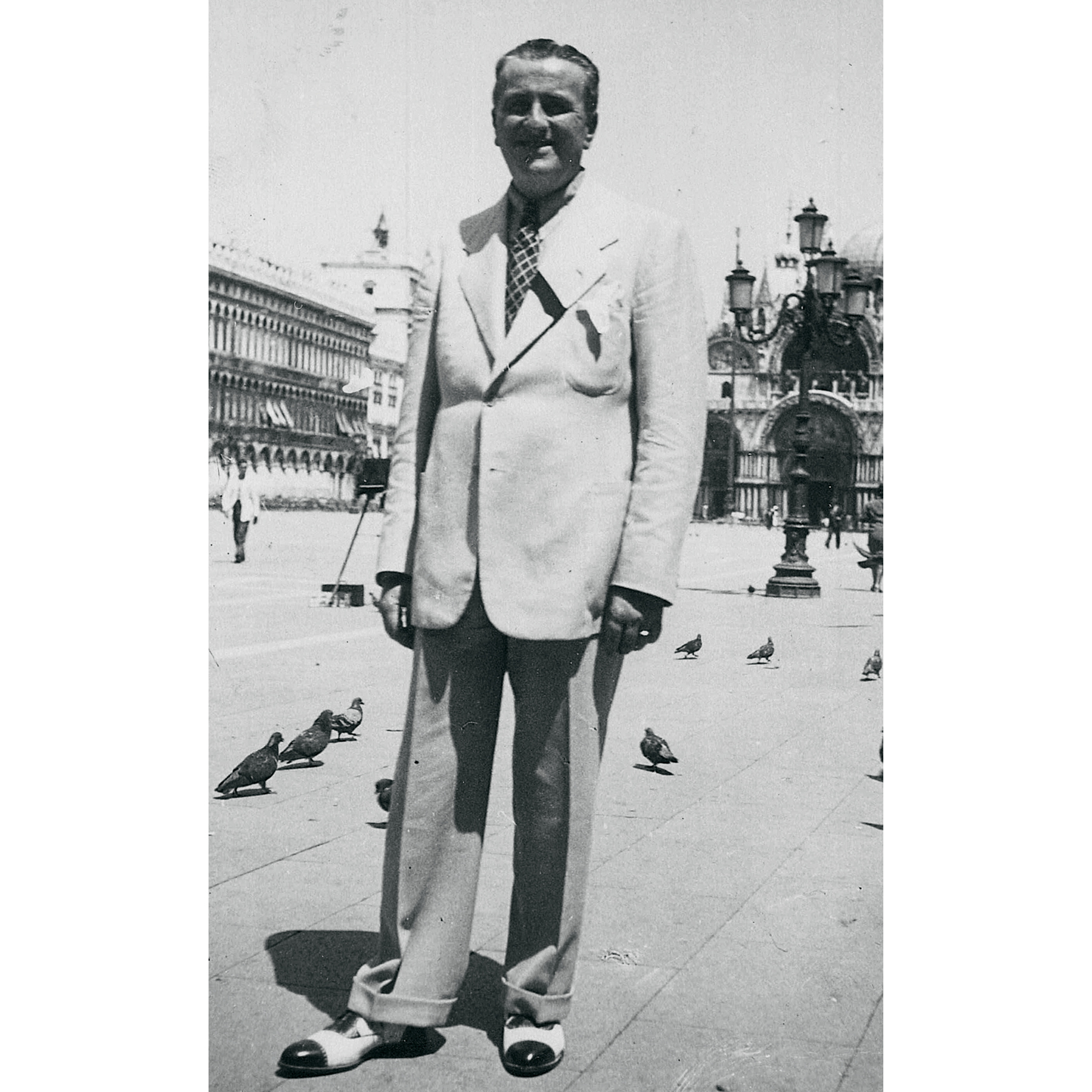

Remaining fiercely loyal to the theatrical spirit of the Seicento, Mario Codognato—the third generation of the family, active from the 1920s until his death in 1949—brought new life to the fantastical and macabre.

He revived the grotesque not as mere ornament, but as a provocative aesthetic statement, weaving together Baroque extravagance and a modern flair for the unsettling. His creations were bold, defiant pieces: eerie memento mori rings adorned with enameled skulls, some crowned or wreathed in laurel like ancient emperors resurrected from the underworld. Using oxidized silver and rich yellow gold, he heightened contrast and drama, often setting the hollow sockets of death’s heads with glinting diamonds—turning horror into opulence.

Alongside these vanitas-themed jewels, Mario assembled a surreal bestiary: jointed serpents that slithered around the wrist, grotesque toads with gaping mouths, rats poised in frozen mischief. These pieces were not quaint curiosities, but uncanny relics designed to confront beauty with decay, desire with dread.

Remarkably, during the interwar years—and especially the 1930s—his shadowy, theatrical vision found devoted admirers across Europe. Far removed from the polished conventions of Parisian or London jewelry, Codognato’s work attracted a circle of avant-garde icons who relished its dark poetry. Artists, performers, and intellectuals sought him out: Sergei Diaghilev, Jean Cocteau, Jean Marais, the dancer Serge Lifar, and even Coco Chanel were among those who were seduced by his subversive craftsmanship.

In a world increasingly fractured by war and disillusionment, Mario’s jewelry offered an intimate, wearable rebellion against bourgeois norms. Here, a ring could contain an ivory coffin with a secret hinge—opened with a flick of the finger to reveal some hidden symbol or message. These were not accessories; they were talismans of mortality, drama, and identity.

By the late 1940s, as Europe emerged from the shadow of war, Venice once again became a place of personal and creative rebirth. Among those drawn to its faded splendor was Ernest Hemingway, who arrived in the fall of 1948, nearly fifty and seeking both inspiration and escape. It was here that he met Adriana Ivancich, a striking young Venetian whose presence awakened a dormant intensity in the writer. Their relationship—simultaneously paternal, romantic, and artistic—spanned continents and shaped his final works. Venice, with its layered history and air of exquisite melancholy, became the stage on which Hemingway confronted aging, desire, and loss. Adriana would inspire Renata, the youthful muse in Across the River and Into the Trees, a novel imbued with nostalgia and fatalism. In Across the River and Into the Trees, Hemingway captures a moment of fascination in front of a jeweler’s window.

Attilio Codognato’s life was shaped by two intertwined passions—art and jewelry—twin threads that guided his eye, his craft, and his sense of beauty.

Attilio was only eleven when his father passed away, too young for the kind of guidance or training that might have been passed down. In fact, he might never have gone into jewelry at all had his father not died so early.

A decade later, at the age of twenty-one, he encountered the remarkable jeweler Enzo Salvati, who became a formative figure in his life. Salvati was an exceptional and imaginative craftsman, and his influence proved decisive. In 1958, Attilio assumed responsibility for the family business.

Though circumstance led him into jewelry, it was art that first captured his imagination and remained his deepest and most enduring passion. One of Attilio’s earliest and most vivid memories came not from a museum but from the streets of Milan. After the war, while playing football outside a shop, he accidentally broke the storefront window with a ball. Behind the shattered glass was a painting by Giorgio de Chirico. The gallery belonged to Vittorio Emanuele Barbaroux, who reacted not with anger but with purpose. He pulled Attilio inside by the ear and made him view the entire collection. It was a moment of reckoning and perhaps the true beginning of his love for art. Attilio’s first acquisition came shortly after.

At just eighteen, he bought a work by Lucio Fontana for the equivalent of a modest trattoria dinner—five dollars at the time. It was the start of a collection shaped not by fashion, but by instinct and a sense of proximity.

By the 1960s, Attilio was spending several months each year in New York, where he formed lasting relationships with leading art dealers such as Ileana Sonnabend and Leo Castelli. Around the same time, Attilio opened a small pop art gallery in Venice, the Galleria del Leone. The gallery opened with a Fontana exhibition, followed by Cy Twombly and Gerhard Richter. In 1963, he hosted Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s first exhibition in Venice, which featured wrapped objects bound in cloth and rope.

Over the years, Attilio developed close relationships with major artists, including Andy Warhol, who painted his portrait and mentioned him in his diaries, describing a 1977 dinner in his Venetian palazzo. The party went on late into the night, even after an earthquake shook the building and sent guests and artworks tumbling.Although he only visited Venice a few times, his connection with Attilio endured. Over the years, Attilio assembled a collection that included not only Warhol, but also Rauschenberg, Bruce Nauman, and Twombly. Of all his collected artist, however, his admiration for Marcel Duchamp remained strongest.

This admiration was influenced in part by Arturo Schwarz, a Milan-based gallerist with whom Attilio became close. Schwarz played a pivotal role in introducing him to Duchamp’s work and worldview. During the 1960s and ’70s, Attilio acquired some of the Duchamp works still available. In addition to Duchamp, Schwarz also encouraged him to collect works by Picabia, Dalí, and others from the surrealist circle.

Attilio did in fact meet Dalí—but not as a fellow collector or admirer. Dalí was a client. Though brilliant and highly intelligent, he was also theatrical. When Attilio published Antologia Grafica del Surrealismo in 1975, Dalí was notably missing from the volume. As a key surrealist figure, his absence was certainly noticeable. Dalí agreed to participate, but only under specific terms: he told Attilio to come to the Hôtel Le Meurice in Paris with $30,000. A month later, Attilio brought the money and asked what Dalí had in exchange. The artist offered a watch, considering it a symbolic contribution—especially because Attilio, as a jeweler and goldsmith, could transform it into something meaningful. What resulted was a bold surrealist jewel featuring horses—a loud, eccentric piece that was eventually lost.

The deep interconnection between Attilio’s lifelong passions—jewelry and contemporary art—was captured with remarkable clarity in 2022 by the photographer Juergen Teller. The shoot, set inside Attilio’s Venetian home, was more than a portrait of a legacy; it was a living tableau of everything Codognato represents. At its center stood his grandson Andrea, wearing Codognato’s jewelry (rings, bracelets, and Vanitas pieces layered with symbolism and history) while standing on Piero Manzoni’s Base Magica—Scultura Vivente. Manzoni’s work, a conceptual plinth that turns the person atop it into a living sculpture, echoed Attilio’s own vision of jewelry as something more than adornment—something performative, intellectual, and existential. The image collapsed boundaries: between generations, between art and ornament, between the living and the symbolic. Teller’s photograph was not simply a tribute to a family tradition, but a crystallization of the Codognato ethos—rooted in Venice, steeped in history, yet always engaged with the avant-garde. In that moment, past and present converged: a grandson elevated by art, adorned in memory, and carrying forward a legacy that has never ceased to evolve.