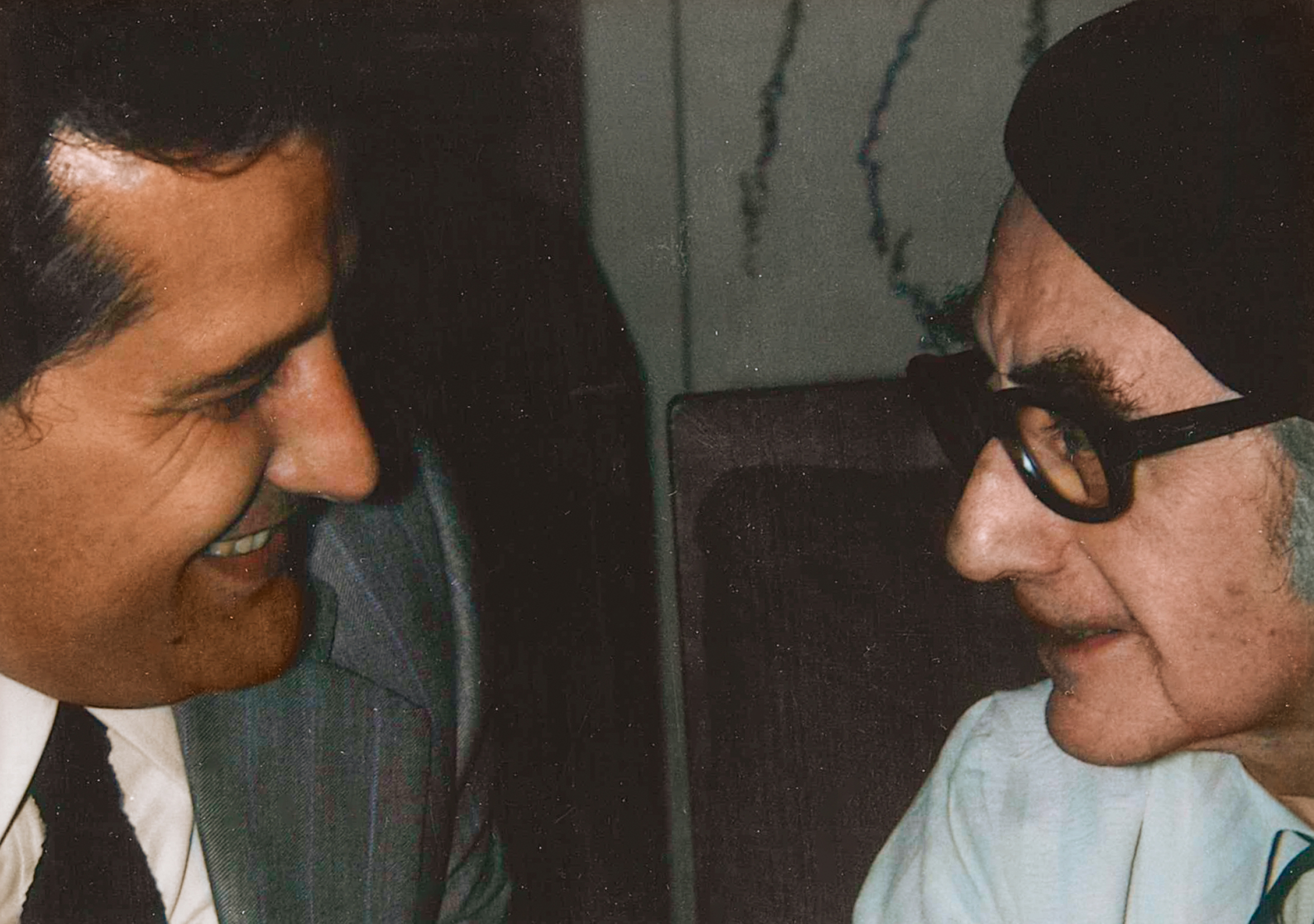

The chess player who confronts the naked woman. Marcel Duchamp, the great artist. Or Attilio Codognato, the Venetian jeweler, the man who loved playing with beauty.

The chessboard as the alchemical table for the game of naked, authentic life, one you do not win and do not lose, one that does not predict the end of time. Knowing the moves of the oldest stories and having a new strategy every time so as not to lose the grace that is hidden in plain sight, like a blunder or perhaps only a phantom. Confronting beauty and desiring to reach it, hone it, strip it of every ornament, touch it with the style of intelligence, imagining it, remembering it, manipulating it, brushing against it, daring and deceiving, this is real style, abstract taste, the ever-deferred conceptual pleasure of knowing your way around.

In that famous photo of Marcel Duchamp, Attilio Codognato, smitten with the older artist, sought traces of it everywhere, as well as the fate of the collector and, above all, of the man who pursued the art of precious things, seated with his gaze fixed on the chessboard of time, to keep the mirage of beauty from vanishing into flesh and blood. Attilio knew everything about folding and refolding gold, and about stones to be worked and mounted, and about every material to be softened and forged, and at the same time he was passionate about the new art of Warhol, Rauschenberg, Nauman, and Twombly, perhaps the only form of modern thought not hostile to creation, a mental language that confers mutable aspects to beauty because it does not refuse to keep them hidden, difficult to see, esoteric. Attilio, the jeweler, was heir to a restless tradition, floating in the same Venetian water, never truly still, fashioner of a craft as slow as the undertow of the lagoon, full of mysterious tales that come and go between Europe and the East.

Everyone knows that Codognato jewelry has a long history, beginning in 1866 behind Saint Mark’s Square and since that time fostered by art in an antique shop, with paintings and fascinating objects.

His great-grandfather Simeone established the shop, and his grandfather Attilio began making the alchemical mixture of precious materials and unexpected representations, mined from the seventeenth-century imagination of memento mori, skulls, and snakes wrapped in precious metals and stones. These were the years of great archeological discoveries in Etruria, a period when the remote past gave a modern impetus to a desire to gaze in distant and unusual directions. Refined techniques and Byzantine, Roman, and Renaissance cultures, from earrings and skull rings to snake bracelets and ancient cameos: a whirl of eccentric images, glittering original jewels of luminous shadows, infused with mysterious symbols and omens.

This ideal practice of an outdated craft was very much ahead of its time and long overdue, contemporary with an inner life full of ripples, which cannot be seen and is largely imagined, floating in a dense and opaque history, like a sea that experiences no storm and shudders only in the lapping of the deep water. It has turned Attilio Codognato’s biography into something artistic and modern and celebrates his shop with the world—a multifaceted work of an entire lifetime spent playing chess with naked beauty. From great-grandfather to grandfather, and from father to son, Codognato jewelry has been and remains the site of a mysterious luxury and worldliness without limits, a cave of miracles that embodies Venice, indeed embeds it like a precious stone in a setting chiseled by a lineage of craftsmen trained independently of chronological time. Nor is what one sees or thinks one sees that important, crossing the threshold of the old workshop, a stone’s throw from Saint Mark’s Square. And like discovering from a fissure in Marcel Duchamp’s final work something that looks like a landscape, something that has something to do with dream, perhaps

with life, perhaps with art.

An idea of beauty that no one would know how to reproduce or describe with absolute certainty.

The solemn names of the women and men who would still become infatuated with it, after Coco Chanel, Luchino Visconti, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Jean Cocteau, Elizabeth Taylor, and Maria Callas, bear witness to the world-wide obsession of those who want the best, that no one can possess it forever. The fate of things that are truly precious is to be unique in their infinite difference, to shine as if nothing had happened before or after.